Under the overhead lights, on a bed in the pediatric catheterization lab on the fifth floor of the University of Iowa Stead Family Children’s Hospital, a half-dozen doctors stared at a clump of translucent silicone, about the size of a child’s fist.

.

The doctors wanted to fix a 10-year-old girl’s defective heart without using scalpels. But they weren’t sure their technique would work, worried that a replacement valve would fall out of place and block other arteries.

.

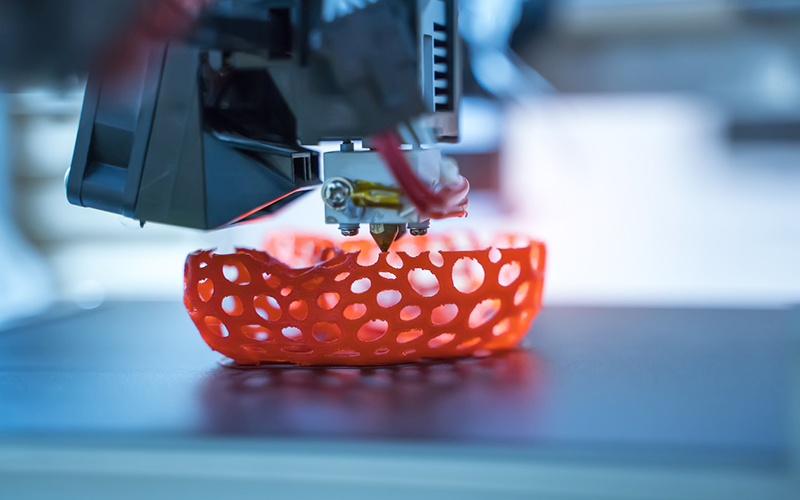

So the doctors practiced on a 3D-printed custom replica of the girl’s organ, a kind of dress rehearsal university officials hope will become more common in Iowa as the state invests in a new, $500,000 printer.

.

The girl had a leaky pulmonary valve. Every time her heart compressed, a little less than half of the blood slipped back into the pumping chamber. The chamber had doubled in size. Her heart was out of rhythm. She grew tired faster than her friends when they played volleyball.

.

A surgeon could have stepped in: hooked her up to a heart-lung machine, cracked her sternum, sliced open her chest, fed cold fluid into her heart until it stopped, cut an artery, inserted a new valve, sewed up the artery, warmed up and restarted the heart, and then closed her chest. .

Case Study: How PepsiCo achieved 96% cost savings on tooling with 3D Printing Technology

Above: PepsiCo food, snack, and beverage product line-up/Source: PepsiCo PepsiCo turned to tooling with 3D printing...

0 Comments